By Joe C. Paschal, Professor Emeritus and Livestock Specialist.

The New World Screwworm is actually not a worm but a fly that lays its eggs in an oval, shingle like white mass in the fresh wounds, and sometimes the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and vulva, of warm-blooded animals. The fly can lay a few hundred or a few thousand eggs in its lifetime. The eggs hatch in a few hours and the larvae begin to burrow into the wound, feeding for 4 – 10 days. After that period, they drop to the ground and form a pupa for 7 days and then emerge as an adult screwworm fly.

The New World Screwworm is actually not a worm but a fly that lays its eggs in an oval, shingle like white mass in the fresh wounds, and sometimes the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and vulva, of warm-blooded animals. The fly can lay a few hundred or a few thousand eggs in its lifetime. The eggs hatch in a few hours and the larvae begin to burrow into the wound, feeding for 4 – 10 days. After that period, they drop to the ground and form a pupa for 7 days and then emerge as an adult screwworm fly.

The amount of time for each stage may vary slightly, depending on environmental conditions, but generally occurs within a month. The adult fly is slightly larger than a house fly, with large orangecolored eyes, and are blueish green with three large dark stripes on its back. The larvae of screwworm can be identified by two dark lines extending from one end down the back but any suspected case should be taken or sent to your local or state animal health veterinarian for accurate identification. The screwworm fly was once native to most of the Southern US but was eradicated by the use of the sterile insect technique developed in the 1950s.

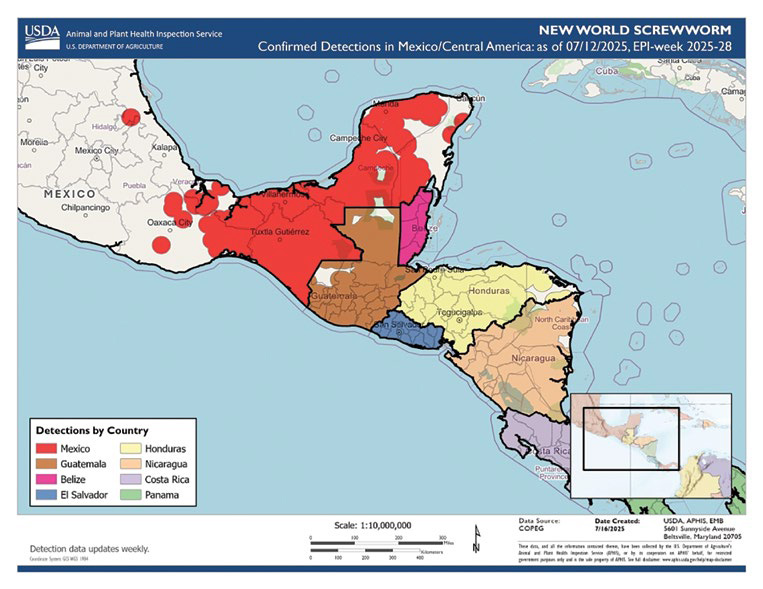

Screwworm larvae were irradiated, sterilizing both sexes. The flies were then released into infested areas to mate with wild flies. Since the female fly only mates once, when she mated with a sterilized male fly, all of her eggs were sterile. As a result, the fly was slowly eliminated over the next 50 years from the US (1967), Mexico, and finally in Central America (2006). Education of producers to recognize, report, and treat animals infested with screwworms was very effective alongside an active production of sterile screwworm flies in eradicating and controlling this awful pest.

I am not sure what has changed to create this situation but certainly a lack of vigilance and preparedness are among the top reasons. The infestations on livestock are not only caused by management practices but could be caused by tick infestations, especially the Gulf Coast tick (a hard backed tick that feeds on the tips and outsides of ears) and the Spinose Ear tick (which is a soft back tick that infests the inner part of the ear). Screwworms are most active in the warmer months so livestock activities that can draw them were in the past moved to the fall and winter months (dehorning, castrating, branding, ear notching, tagging, implanting, and even calving as the flies were attracted to the newborn calf and post calving vulva discharges). This will be especially critical for dairies and intensive farrowing or lambing operations as well as calving beef cows.

Livestock and other animals including pets, poultry, and people can be infested. Wildlife are not immune, especially buck deer in velvet or rut, and wildlife (native and introduced) are especially difficult if not impossible to treat. The animal has to be caught, the maggots removed, and treatment to kill the worms and heal the wound applied. Cases should be kept in smaller pastures or pens for ease of observation and treatment. The maggots burrow deep into the flesh and often can be found under the skin next to the initial wound. The smell of a bad screwworm case is indescribably awful! Screwworms cannot fly far but wind, especially hurricanes, can move them quite a distance and quickly. The US was declared free in 1967 but due to the pressure of the large screwworm population in Mexico, Texas had over 90,000 cases.

It took several years for the US to become screwworm free again. There are a number of products on the market that will kill the infestations in the wounds including those that contain permethrin and coumaphos but also Essentria IC Pro® (for facilities) and Arkion Fly and Tick Spray®. There has been some interest in using the macrocyclic lactones (Ivomec® and Decotmax® which are used in the Cattle Fever Tick Control Program), but as of this writing they are not included. The use of standard horn fly control products (tags, pour-ons, dust bags, back rubbers, traps, etc.) will help reduce but not eliminate the threat, however increased vigilance of the presence and types of flies and ticks on your livestock and rapid observation and treatment of wounds is highly recommended.

Let us hope that this menace gets controlled before it reaches our borders. There are several educational websites with information on the screwworm (identification, treatment, and reporting) including the Texas Animal Health Commission, USDA Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service, and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. I would also recommend the website for The Panama–United States Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm Infestation in Livestock (COPEG) www.copeg/org