By Joe C. Paschal, Professor Emeritus and Livestock Specialist

By Joe C. Paschal, Professor Emeritus and Livestock Specialist

We are all accustomed to having some cows (20-40%) come back into heat after breeding, but if the breeding season is long enough, there is a good chance she will return to estrus and get rebred. There are a number of reasons this can happen, even in well managed cows.

Reproductive physiologists call these early embryonic losses (EEM), but since they happen early in the breeding season (and the cows usually rebreed successfully), they are of less consequence than those that happen between 30 and 90 days as the breeding season ends. These losses (3 – 8%) are called late embryonic mortality (LEM) and can have a significant impact on cow productivity. These losses can have lasting impact on cow productivity and herd performance. Some causes of LEM include reproductive disease, handling or environmental stress, nutritional (energy or mineral) deficiencies and genetics.

A recent article from the University of Georgia Beef Team evaluated how LEM affects cow productivity long-term in cow-calf production. The study included 2,204 cows from six locations in four states (Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee and Virginia). All cows were bred using fixed time AI (FTAI) and then exposed to cleanup bulls for the remainder of the breeding season, which ranged from 67 to 86 days. After calving, the cows were assigned to one of three groups:

1. Maintained – cows that maintained their AI pregnancy,

2. Non-pregnant – cows that did not become pregnant to AI (but may have been bred to clean-up bulls), and

3. LEM – cows that lost their embryo between one and three months of gestation. Cows in groups 2 and 3 could have been open or had a calf from a cleanup bull.

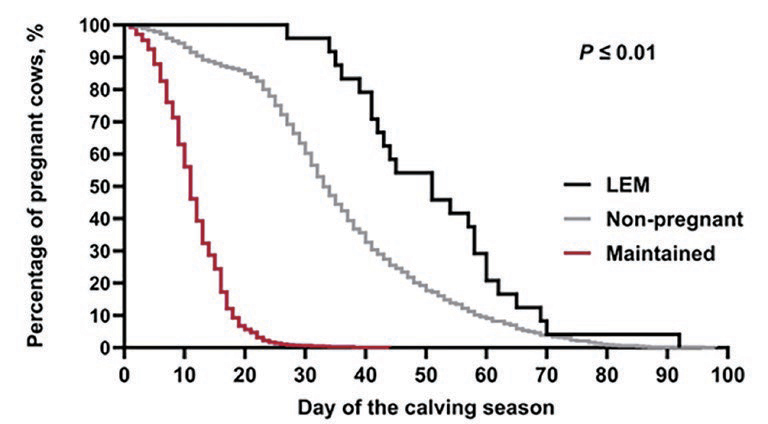

The cows were studied for two years to determine subsequent effects on performance. As one can surmise, cows that experienced LEM had significantly decreased pregnancy, calving and weaning rates compared to the first two groups.

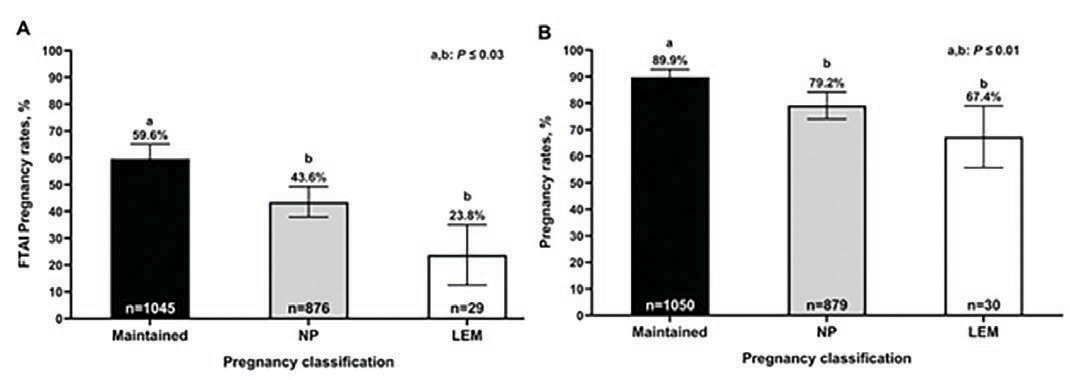

In the following year, cows that had LEM calved significantly later and had significantly lighter calves compared to the first two groups. In addition, both the non-pregnant (group 2) and the LEM cows had significantly decreased pregnancy rates to FTAI and final pregnancy rates compared to the cows that maintained their FTAI pregnancy (group 1). This would indicate a heritable genetic condition that predisposes cows to either be fertile and maintain a pregnancy or to be subfertile or infertile. A difficult task when flushing embryos from heifers that could further reduce fertility in a breed.

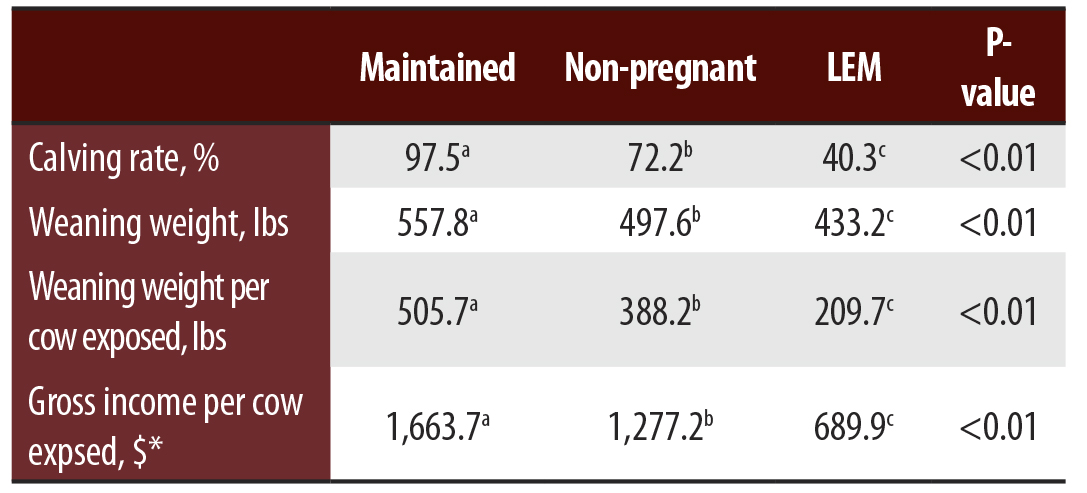

Cows that experienced LEM had substantially decreased cow productivity than either of the other two groups. The occurred because only about 40% of the LEM cows got bred and calved. In contrast, 70% of the cows that lost their calves early and rebred to the clean-up bulls (group 2) calved. Later calves were younger and lighter at weaning. Calves from LEM cows were 64 pounds lighter from the non-pregnant (group 2) cows and 125 pounds lighter from the maintained (group 1) cows (see Table 1).

The effects of LEM were seen in the following breeding season. LEM cows calved later and were less likely to recover before the next breeding season began so they were less able to respond to FTAI, indicating that LEM impacts lifetime productivity (Figure 2). There was a 16% difference in pregnancy rate between the maintained and non-pregnant groups (A) at FTAI, this was later reduced to 10.7% using clean-up bulls (of lower genetic potential and having later and lighter calves).

Cows that did not get bred or lost their calf early (group 2) were still lower performers to FTAI. Additionally, only 23.8% of cows experiencing LEM the first breeding season bred to FTAI the next year. Using market data from the USDA Georgia Livestock Market Report (8/15/2025) the authors reported a loss of $963 per cow exposed for the LEM group compared to cows that maintained their pregnancy. Certainly something to consider! To access the entire report, go to: Lucas and Pedro – https://beef.caes.uga.edu/ fi les/2025/08/Lucas-and- Pedro-May-2025-1.pdfay 2025

Scan QR code to access entire report referenced in the article.